What, would you say, is the main difference between a piano note and a flute note? You might suggest that it has something to do with the shape of the note — a piano note is struck once and then simply held down, while a flute player has to actively blow throughout the duration of the note.

In part 2 of this series on what makes a musical sound, we looked at how the frequency content of a note affects its timbre – the tone quality that allows us to distinguish between different instruments. But the shape that we were just talking about also contributes to how a note sounds, and I’ll talk about this today. I’ll also explain how musicians can vary the timbre of their sound using different playing techniques.

The Envelope of a Note

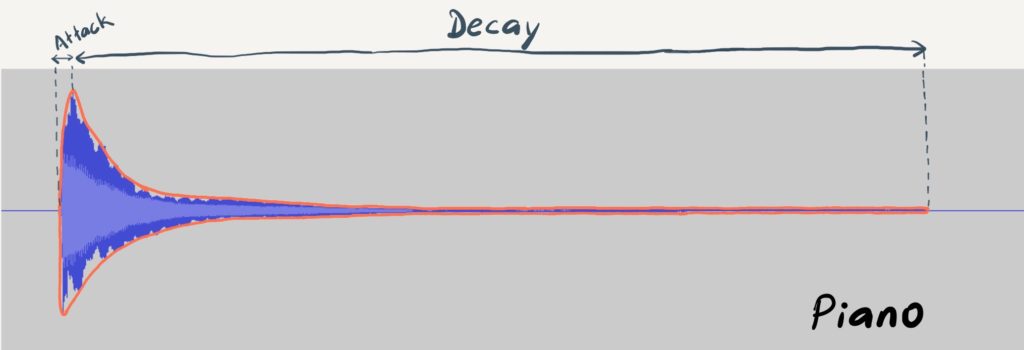

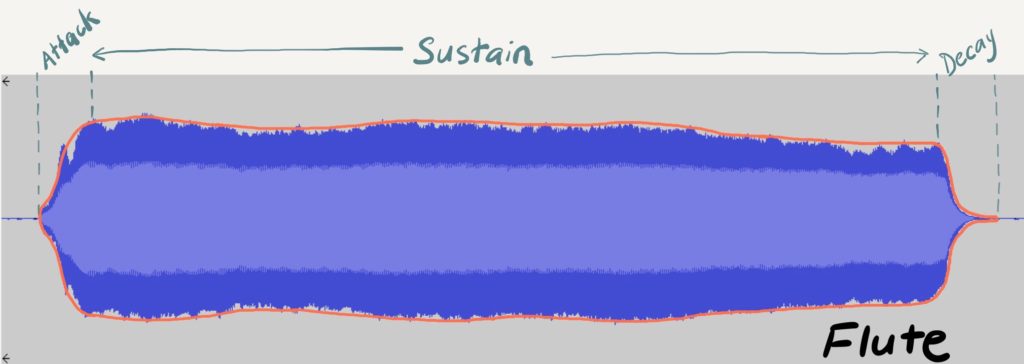

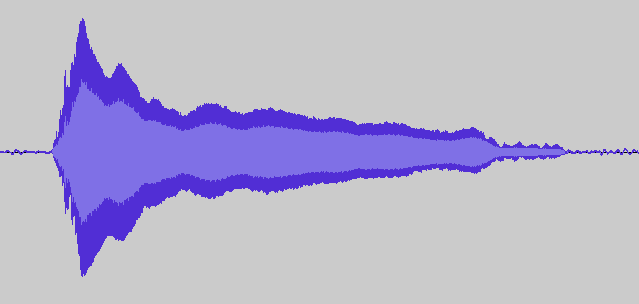

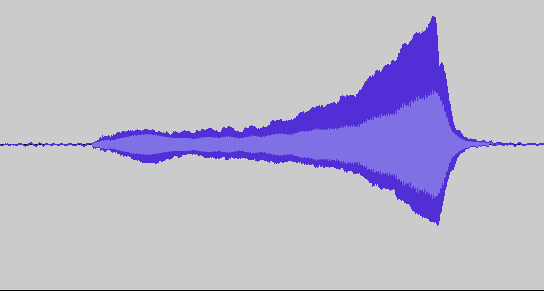

We can see the shape of the piano and flute notes by looking at their waveform:

In these pictures, we’re zoomed out on the time axis so that we can see each note over its entire duration. In this zoomed out state, we can’t see the individual curves of each vibration of the wave, but we can see the general shape that we would get if we were to draw a line through the highest points of the wave (and another through the lowest). This shape (marked in orange) is called the envelope, and it shows how the note’s loudness, or amplitude, changes over its duration.

A piano note starts when the key is struck and the hammer hits the strings. It slowly decays off, getting softer, until the key is released. This causes a damper to fall back onto the strings, silencing the note. The envelope of a piano note shows this abrupt onset (or attack) and slow decay. A flute note, however, has a smoother attack and long sustained part, followed by a short decay.

To further illustrate the difference between the flute and piano, we can listen to what happens when we play piano and flute music backwards. In the following clips, each instrument first plays normally, then the sample is played backwards:

The backwards flute sample doesn’t sound that far off from a flute (though perhaps a little bouncier than someone would normally play it), while the backwards piano sample sounds like some sort of strange futuristic organ! This is because a flute note’s envelope is more or less symmetric in time, unlike that of a piano note.

Controlling Timbre While Playing

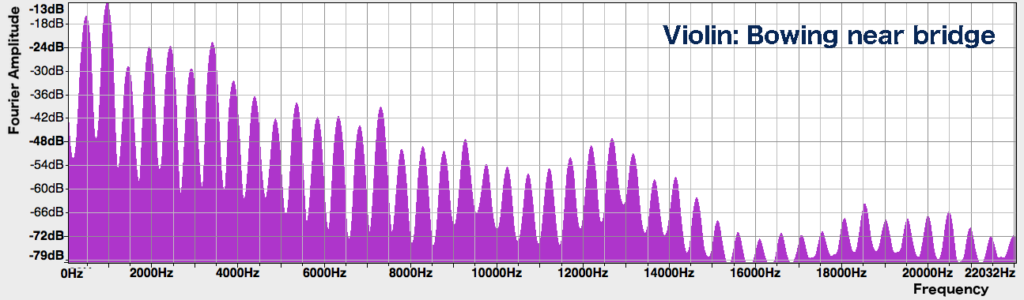

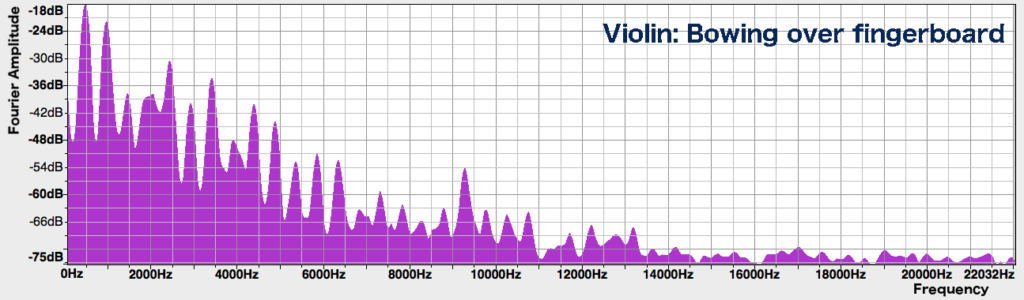

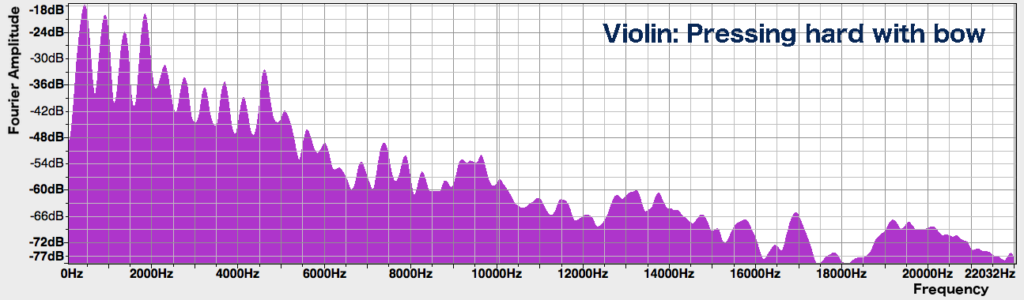

Quite apart from allowing us to distinguish different instruments, a note’s timbre can be varied by the musician to make things more interesting. Have a listen to the following violin notes (some of these hurt the ears, so be warned):

As we saw, the spectrum looks quite different depending on the bowing technique used. A violinist can also vary the envelope of a note:

Vibrato – Wobbly Notes

One notable technique commonly used by string, wind, and voice performers alike is vibrato – this is a wobbling that the musician introduces to the sound. String players do this by moving their finger up and down as it rests on the string; wind players can wiggle either their diaphragm or embouchure, and singers wiggle either their diaphragm or vocal cords (depending on their style of singing).

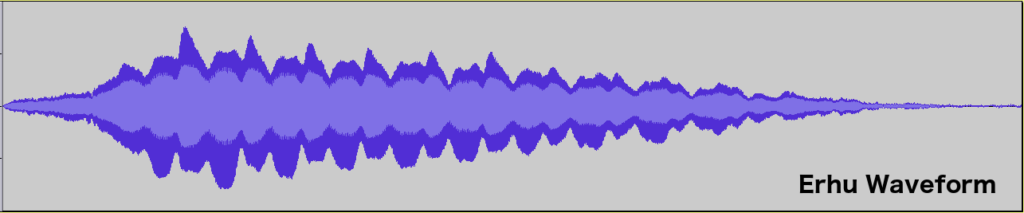

This wobble, or modulation, that is introduced to the sound can be a wobble in either frequency or amplitude (usually both at the same time). Have a listen to this note, played on an erhu (a Chinese two-stringed violin):

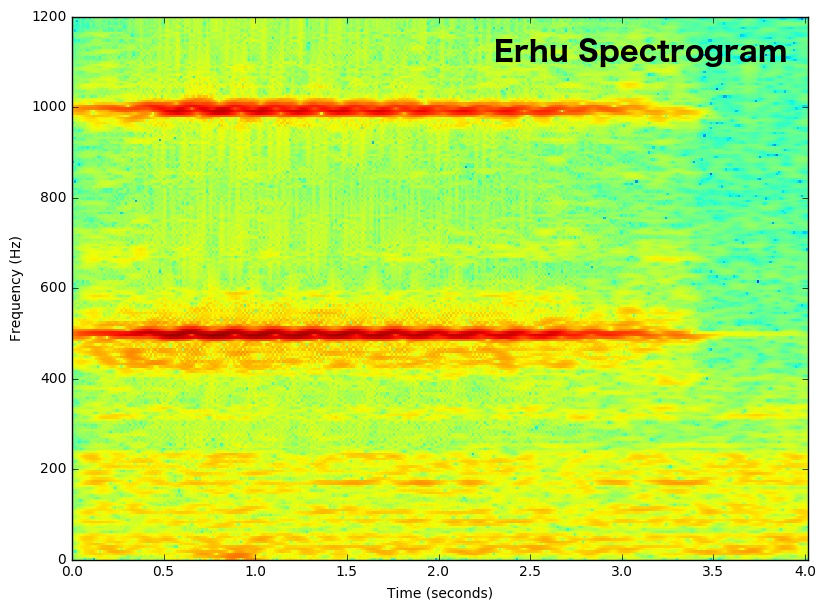

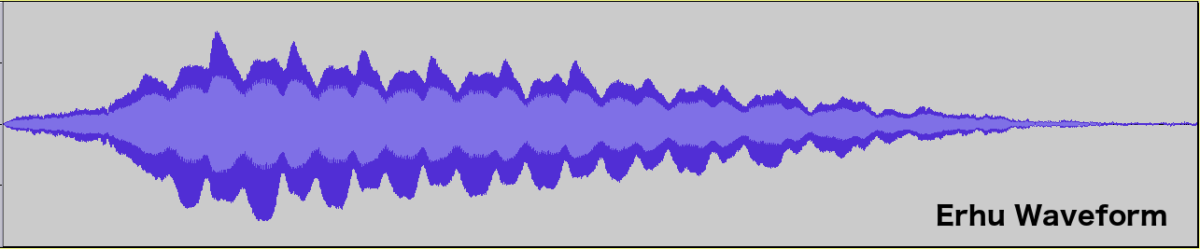

Now take a look at its envelope and spectrogram (which shows how its frequency content varies with time):

We can see from the spectrogram that the note is wobbling up and down in pitch, and from the waveform envelope that it’s also getting louder and softer at each wobble.

Vibrato can only be used in instruments where the player controls the note over its whole duration – it can’t be applied on a piano, for instance. Just how much vibrato to use, and the speed and depth of the vibrato, depends on the style of music and the personal taste of the player, and can even be a matter of contention! Modern players of western classical music tend to use vibrato a lot, but this was not always the case – during the baroque period, for instance, vibrato was only used sparingly to give some notes a different feel. The gradual change to a more frequent use of vibrato was heavily criticised by some, with one composer describing players as “trembling consistently on each note as if they had the palsy”! I personally like the sound of a tight, quick vibrato on the violin, but when playing the erhu I favour a looser, lighter style – somehow I find that strong vibrato doesn’t sit well with the mellow tone of the instrument, and can be rather goosebumps-inducing (in a bad way).

I’ll end this post with a quick summary of what we’ve seen in this three-part series about what makes a musical sound. In the first part, we looked at the basic properties of a musical note — pitch and loudness — and how they relate to the physical properties of the sound wave (frequency and amplitude). In the second part, we studied the spectrum, which shows what frequencies are present in a sound, and which explains why each instrument has a unique tone colour. In this third part, we looked at the envelope of a sound, as well as how musicians can control the timbre of their instruments in various ways. All of these concepts are very useful when studying the science of music, and I’ll certainly refer to them in future posts.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!